How does general anesthesia work?

The short answer

General anesthesia works by disrupting how brain cells communicate, leading to unconsciousness, immobility, and pain relief. While the exact mechanism is still unclear, anesthetics appear to either flood neurons with charged molecules or block them entirely, breaking down communication.

The long answer

Anesthesia can seem miraculous. You go in for surgery, someone places a mask over your face, and asks you to count back from ten. By the time you reach eight, you're waking up in another room all stitched up, disoriented, and with no memory of what happened.

And like any miracle, we still don't fully understand how general anesthesia works.

What does general anesthesia do?

General anesthesia is a reversible, chemically-induced coma that allows you to be unconscious, paralyzed, and pain-free during surgery. An anesthesiologist typically uses a variety of inhaled and/or intravenous drugs to "put you to sleep" and keep you under, while ensuring function of your body's other critical systems.

"Bloc opératoire - IADE" by Hirondus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

When the surgery is over, the anesthesiologist dials back the drugs to awaken you in the recovery room fairly quickly, although you'll remain groggy for a few hours afterwards as the anesthesia wears off. Traces of anesthesia can stay in your system for up to a week, but most people stop noticing any effects after about 24 hours.

What does general anesthesia do to the brain?

At a high level, general anesthesia disrupts communication between neurons in your brain, which makes you unconscious, paralyzed, and pain-free. A common misconception is that anesthesia "turns off" brain activity. But we now know that there's still plenty going on in your brain — the difference is that it's not synchronized between regions.

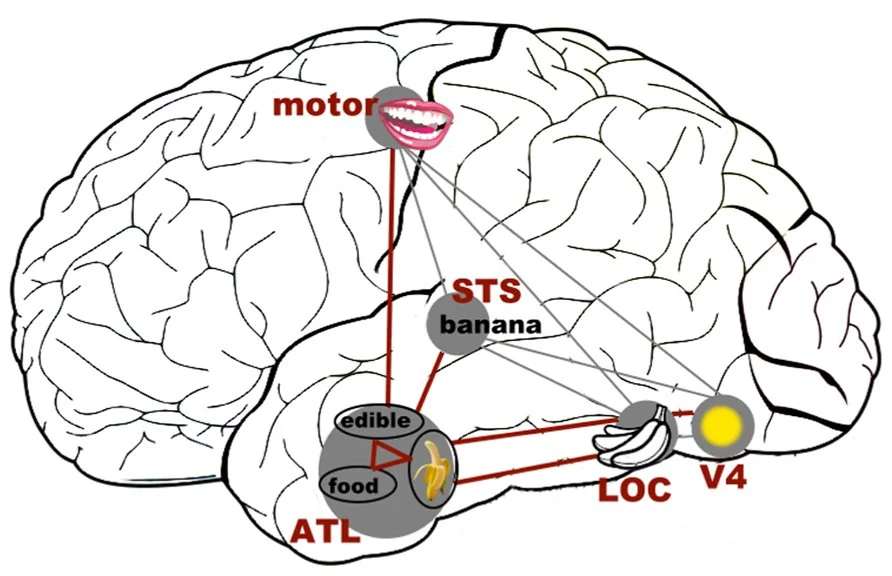

Let's consider how your brain works when you're fully conscious. Specialized areas of your brain process information differently and these data points are synthesized into a single, unified experience.

"A schematic representation of how the (much simplified) concept of a banana as an edible food with its distinct color and shape" by Chiou R and Rich AN is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

For example, when you see a banana, your brain is piecing together data on the color (yellow), object (banana), and the concept of food (edible). Different parts of your brain synchronize their activity, often around 40 Hz, to integrate these data points into a single conscious experience.

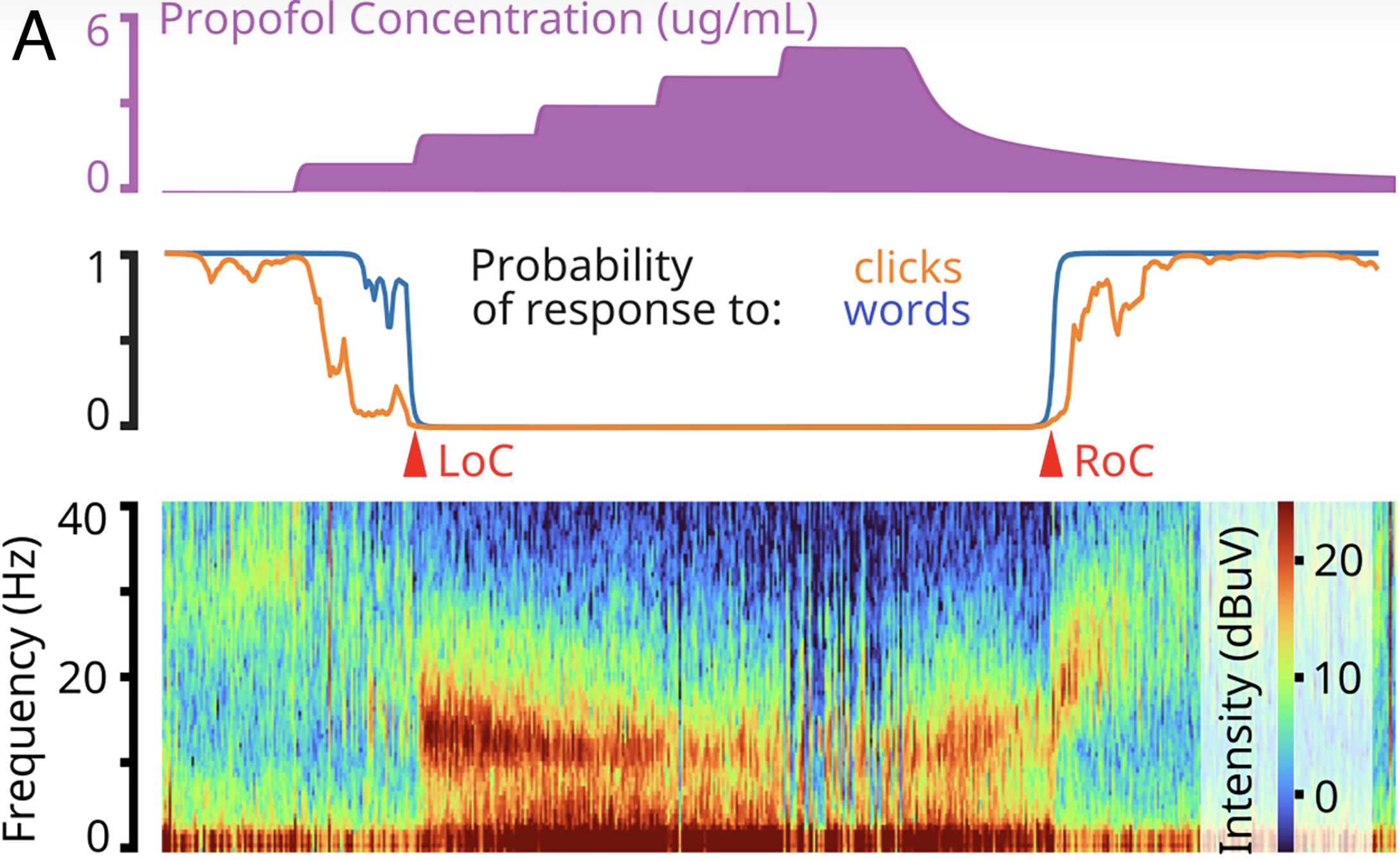

Under general anesthesia, the brain undergoes "cognitive unbinding." While you still have 40 Hz brain waves, anesthesia disrupts the synchronization between brain regions necessary for consciousness.

From top to bottom: These diagrams show how, as the patient receives more anesthesia (propofol) and they lose consciousness (LoC = loss of consciousness), their higher frequency brain waves (40Hz) become quieter.

Source: PNAS

In other words, as you lose consciousness under anesthesia, your brain is still generating activity, but it has lost the synchronization needed for awareness.

How does general anesthesia work?

While different anesthetics work differently, all of them work by disrupting communication between nerves. We don't 100% understand everything happening to knock you out, but here are two leading theories about how general anesthesia works (and likely is a combination of both):

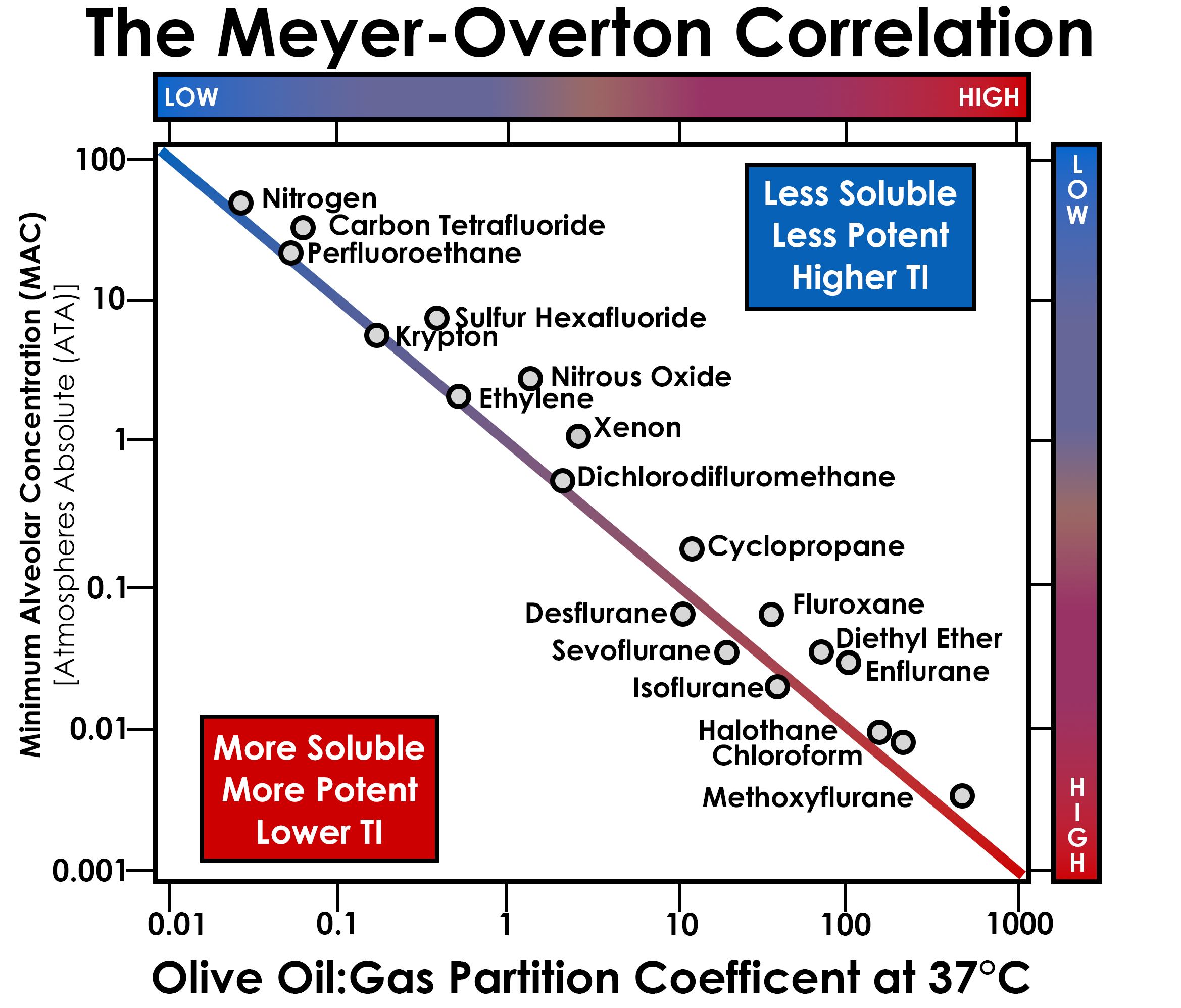

The Lipid Hypothesis

Our cell membranes are made up of oily molecules called lipids. Over 100 years ago, we discovered an interesting correlation: the better an anesthetic performed, the better it dissolved in oil. The Meyer-Overton Correlation suggested that the target of anesthesia drugs was in the fatty membranes of neurons.

The more soluble the agent is, the more potent its anesthetic effect. The X-axis represents the solubility of an anesthetic in oil. The Y-axis represents the minimum dose for effectiveness. Each dot is a common inhaled anesthetic.

"The Meyer-Overton Correlation (Final)" by NeuroImagem is part of the public domain.

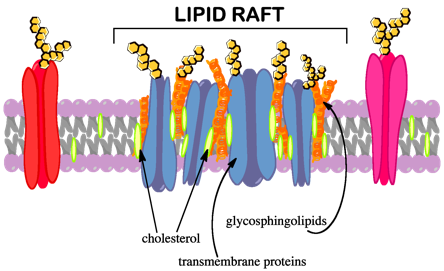

Recent studies have added weight to the lipid hypothesis, showing that anesthetics disrupt "lipid rafts," organized clusters of fat in the cell membranes of neurons.

"Lipid Raft" by Lizanne Koch lgkoch is part of the public domain.

Anesthetics seem to burst these tightly clustered lipid rafts and cause their contents to spill out, including an enzyme called PLD2. The let-loose PLD2 binds to a protein called TREK-1, opening the neuron's ion channels and allowing ions to flood through. This creates a "logjam" of ions that cause the nerve to malfunction.

In short, the lipid hypothesis suggests that anesthetics indirectly disrupt nerve communication, leading to a loss of consciousness, movement, and pain.

The Protein Hypothesis

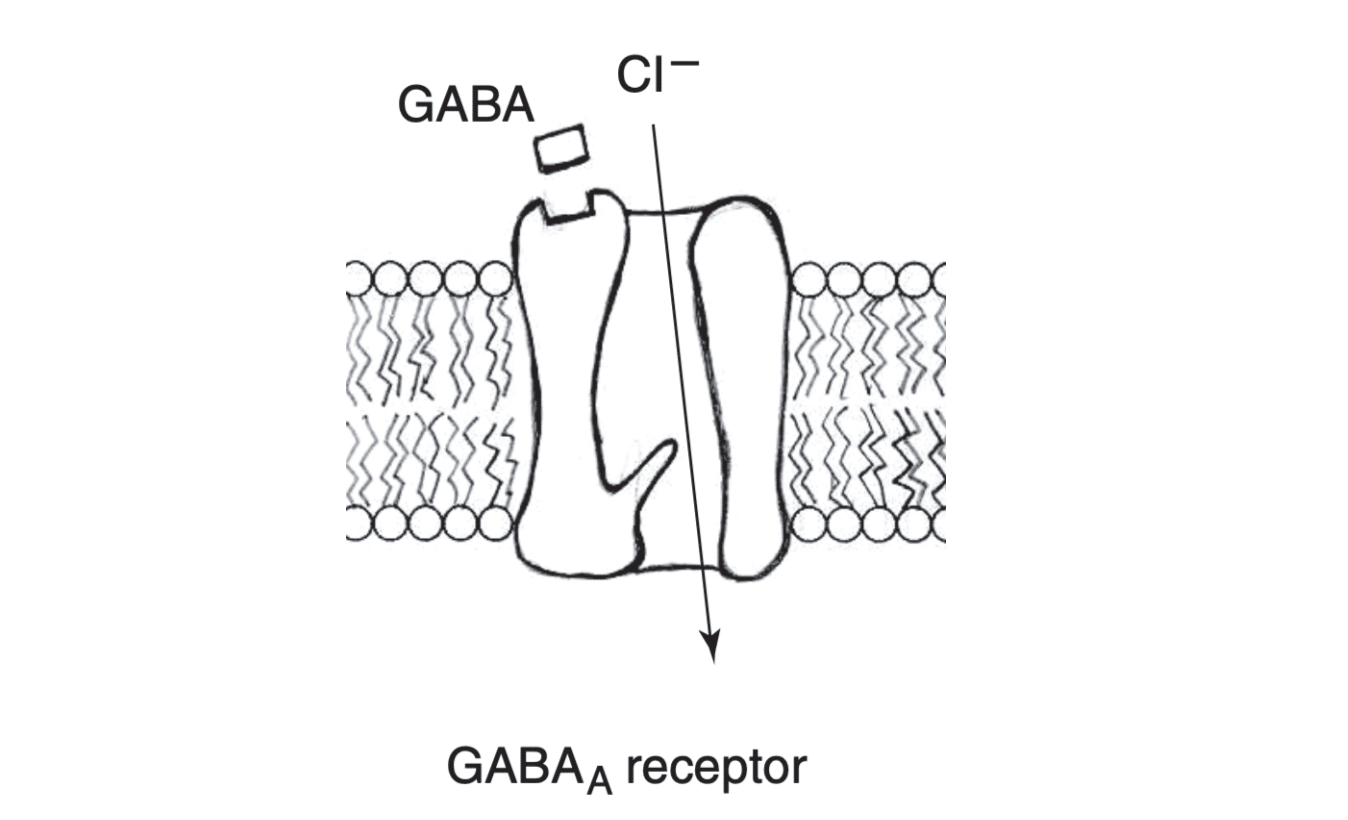

The protein hypothesis doesn't involve the lipid membrane at all. It suggests that anesthetic molecules themselves bind to the ion channel proteins to disrupt nerve function.

For example, several anesthetics bind to GABA-A receptors on neurons, either holding the channels open to let ions flood in and dampen signaling, or blocking ion flow entirely to suppress communication.

This image shows how anesthetics jam the GABA-A receptor open, letting negatively charged chloride ions (Cl-) pour inside. This buildup acts like an electrical "log jam," blocking the signals needed for your brain to stay awake

Source: AANA Journal (Figure 1)

Interestingly, GABA-A receptors play a key role in the brain’s natural sleep mechanisms. These anesthetics seem to achieve a sedative effect by hijacking our natural sleep pathways.

🧠 Bonus brain points

Why do redheads need more anesthesia?

According to the American Dental Association, redheads are more likely to fear dental visits than people with other hair colors. And there's good reason for that: research has shown that redheads have lower tolerance for pain. In fact, one small study revealed that redheads need 19% more anesthetics than people with dark hair. Ouch.

Since only 2% of people worldwide have naturally red hair, research into why redheads need more anesthesia is limited. But we have found a relationship between the gene that produces red hair color and resistance to anesthetics.

While anesthesiologists are aware of this redhead phenomenon, your dentist may not be. Redheads are advised to ask their dentist to give them more anesthetics and more time for them to take effect.

Curious about how the world works?

Today You Should Know is a free, weekly email newsletter designed to help you learn something new every Friday.

Subscribe today 👇

Check out some other curious questions:

Sources

Aranda, M. (2020, September 5). We Finally Know How Anesthesia Works. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZSsYjQeK0qg

Cleveland Clinic. (2024, April 9). Why Redheads May Need More Anesthesia. Cleveland Clinic. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/why-do-redheads-need-more-anesthesia

Georgia Anesthesiologists, LLC. (2016, November 7). Frequently Asked Questions. Georgia Anesthesiologists. https://www.gasdocs.com/faq.php

Green, H. (2015, October 26). What Does Anesthesia Do to Your Brain?. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=43z7NovmlHk

Hansen, S. B. (2025). Mechanisms of general anesthesia. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 94(1), 503–530. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-030222-121430

Mashour, G. A., Forman, S. A., & Campagna, J. A. (2005). Mechanisms of general anesthesia: From molecules to mind. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology, 19(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2005.01.004

Pavel, M. A., Petersen, E. N., Wang, H., Lerner, R. A., & Hansen, S. B. (2020). Studies on the mechanism of general anesthesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(24), 13757–13766. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004259117

Ruder, D. B. (2019, Spring). Anesthesia and the Brain. Harvard Mahoney Neuroscience Institute. https://hms.harvard.edu/news-events/publications-archive/brain/anesthesia-brain

Villars, P., Kanusky, J., & Dougherty, T. (2004, June). Stunning the neural nexus: Mechanisms of general anesthesia. American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology Journal. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15208967/

Yale Medicine. (2019, November 18). General Anesthesia. Yale Medicine. https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/general-anesthesia

Zheng, S. (2015, December 7). How does anesthesia work? - Steven Zheng. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B_tTymvDWXk

Stenographers can type at an 360 words per minute, with an accuracy rate of 99.8%.