Why does stress cause people to overeat?

The short answer

Stress fuels overeating because it triggers the release of cortisol, a hormone that ramps up appetite and urges your body to stockpile energy for future threats, particularly with calorie-dense food.

The long answer

Overeating is a very common response to feeling stressed. In fact, a 2012 survey found that 39% of us overeat or eat more junk food when feeling stressed out. Why does stress cause people to overeat? Let's break this down:

How does stress affect your appetite?

Stress is your body's reaction to potential threats, like a tiger or an all-caps email from your boss. Your "fight-or-flight" response gets your body ready to run from or fight the tiger/email by quickly redirecting its resources.

Both seem like credible threats to me.

During acute stress, the hormone epinephrine (AKA adrenaline) triggers this fight-or-flight response, which suppresses your appetite. It's your body's way of telling you that you have more pressing things to deal with than finding your next meal.

If the threat goes away, your body will adjust back to its normal state and eating habits. But if you remain stressed for a longer period, the hormone cortisol is released. Unlike epinephrine, cortisol increases appetite. Your body is stockpiling energy to help you handle the next threat.

Diagram showing how cortisol rises with repeated moments of acute stress (which trigger releases of adrenaline).

"Demystifying Depression-Cortisol" by Name of Feather is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Your cortisol levels should return to normal baselines when the threat is finally over. But if the stress doesn't go away, your cortisol may remain elevated and cause you to overeat. Chronic stress can even lead to leptin resistance, making you feel hungry even when you've had enough to eat.

But when we're stressed, we don't reach for the carrot sticks. We crave something else...

Why do we crave junk food when stressed?

Humans (and many other animals) respond to stress by eating more foods high in sugar and fat. Why is that?

Reason #1: The body craves energy-dense foods.

In long-term stress, cortisol increases to help you gather up the energy to fight off the next threat. The most energy-dense foods happen to be foods high in sugar, fat, or both. You crave junk food during stress because it's to boost your calorie intake, which you'll need to fight off that tiger or email.

Reason #2: Junk food temporarily lowers stress.

Junk foods get called "comfort" foods for a reason: When you eat fatty, sugary foods, they do seem to calm your nervous system.

Your HPA axis is made up of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal cortex.

"HPA-axis - anterior view (with text)" by Anatomography is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.1 JP.

These foods have been found to temporarily reduce activity in your hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responsible for regulating stress hormones.

Reason #3: Junk food activates the brain's reward system.

Junk food also activates the brain's dopamine pathways, which makes you feel pleasure and relief. This can create a feedback loop wherein we reach for cake when we're stressed because it makes us feel good.

Reason #4: Comfort food reduces feelings of loneliness.

Mac and cheese is my personal comfort food.

"Mac and Cheese (4999893437)" by Vancouver Bites! is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Comfort foods — familiar, often sugary and fatty foods associated with safety and care — truly do seem to comfort us. One study found evidence to suggest that comfort foods can reduce feelings of loneliness, which can help us feel less stressed.

Reason #5: Stress weakens our impulse control.

We also eat more junk food simply because it's harder to resist tempting foods. Stress impairs activity in your prefrontal cortex, which normally helps with impulse control and decision-making. This makes it more likely we'll give in to eating junk food.

What factors make someone more likely to stress eat?

But not everyone overeats when they feel stressed out; some people even report eating less than usual. Your cortisol levels are strongly associated with how likely you are to "stress eat." So what factors into your cortisol levels?

Adverse early life experiences: If you had exposure to stressful life events in your childhood (abuse, neglect, etc.), this can lead to lasting changes in your HPA axis which make you have higher baseline or reactive cortisol levels.

Chronic sleep problems: Chronic short sleep and circadian misalignment (e.g. night shifts) are associated with higher evening cortisol and increased appetite for junk foods.

Dieting: Restricting your daily caloric intake can put your body into a stress state, increasing the total daily cortisol levels.

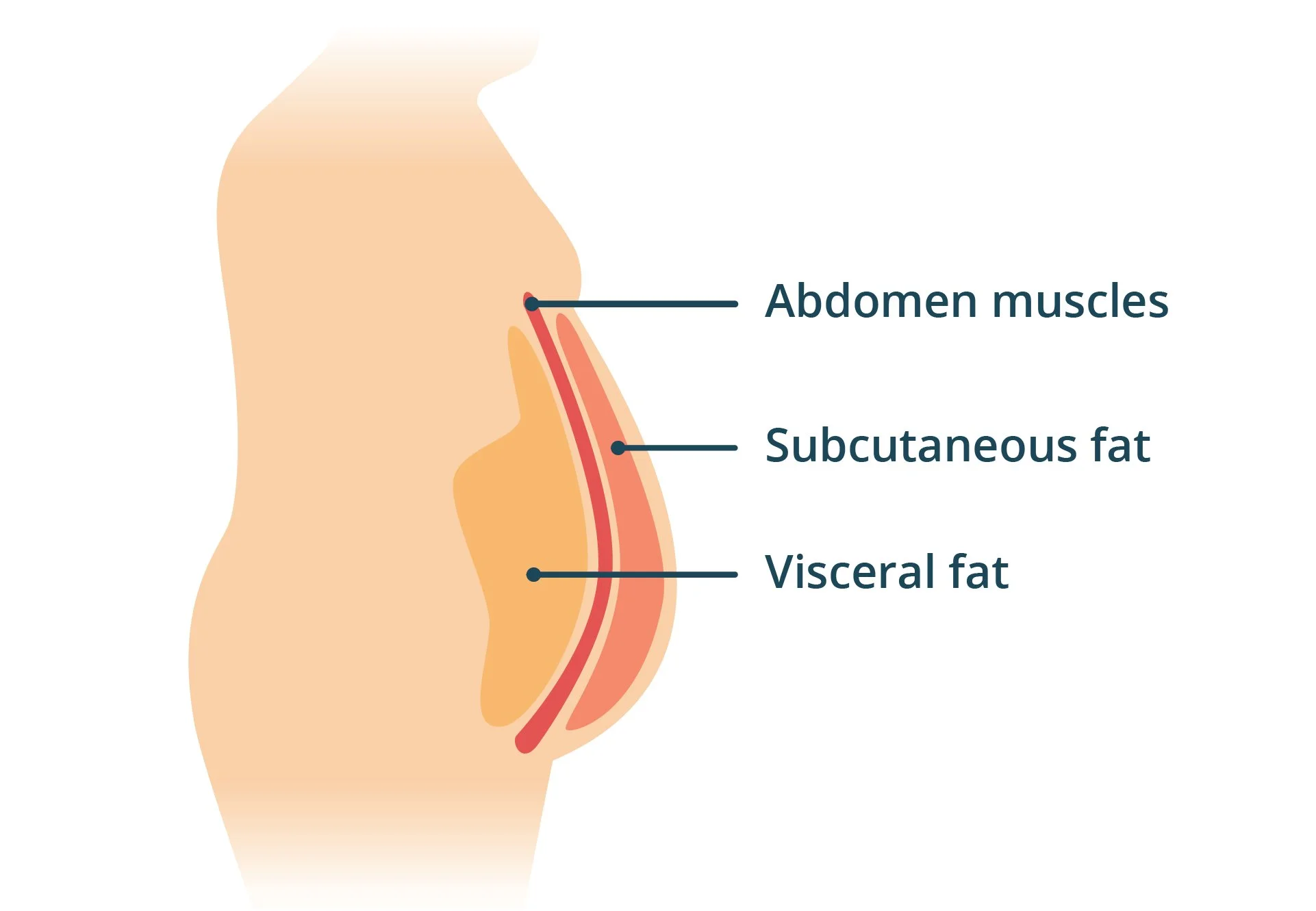

Being obese or overweight: If you have a high body fat percentage, you'll have higher levels visceral fat, the fat around your major organs. Visceral fat is biologically active and actually produces cortisol locally. On average, long-term cortisol levels are elevated in obese individuals.

Source: Healthdirect Australia

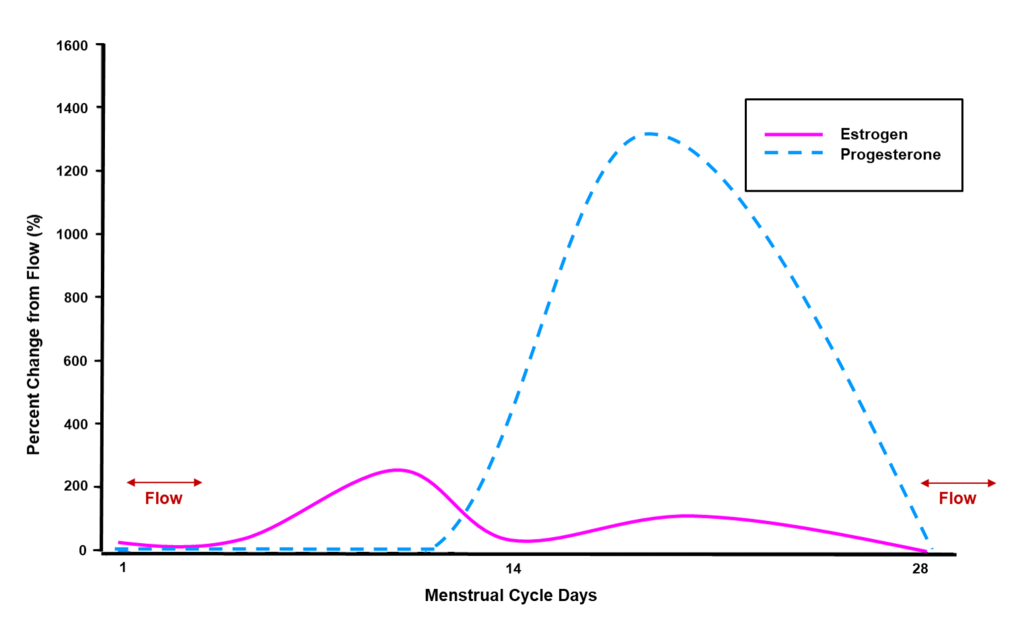

Being a woman: Women are more likely than men to turn to food as a way to cope with stress. Part of the reason for this is how female reproductive hormones play a role in the body's stress system.

During the menstruation cycle, hormones estrogen and progesterone rise and fall. When estrogen is high (around ovulation), it lowers your appetite and can even dampen cortisol's effects. But progesterone does the opposite: When progesterone spikes (after ovulation), this hormone increases appetite and can make our stress response more reactive. This may explain why menstruating women often crave sweet foods about 7-10 days before their periods.

"Estradiol and progesterone % changes across the menstrual cycle" by Dharani Kalidasan MSc and Jerilynn C. Prior BA, MD, FRCPC is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Curious about how the world works?

Today You Should Know is a free, weekly email newsletter designed to help you learn something new every Friday.

Subscribe today 👇

Check out some other curious questions:

Sources

Asarian, L., & Geary, N. (2006). Modulation of appetite by gonadal steroid hormones. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 361(1471), 1251–1263. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2006.1860

Cui, S., & DiMichele, E. (2024, August 31). Stress and Binge Eating: Why We Do It and How to Avoid It. National Center for Health Research. https://www.center4research.org/stress-binge-eating-avoid/

DeSimone Wozniak, J., & Huang, H. (2025, March 6). Considerations for the Role and Treatment of Emotional Eating. Harvard Medical School. https://info.primarycare.hms.harvard.edu/perspectives/articles/emotional-eating

Harvard University. (2021, February 15). Why stress causes people to overeat. Harvard Health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/why-stress-causes-people-to-overeat

Juruena, M. F., Eror, F., Cleare, A. J., & Young, A. H. (2020). The role of early life stress in Hpa Axis and anxiety. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_9

Prado, R. C., Oliveira, T. N., Saunders, B., Foster, R., de Jármy Di Bella, Z. I., Kilpatrick, M. W., Asano, R. Y., Hackney, A. C., & Takito, M. Y. (2025). Effects of the menstrual cycle phase on cortisol responses to maximum exercise in women with and without premenstrual syndrome. Endocrines, 6(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines6010014

Tomiyama, A. J., Mann, T., Vinas, D., Hunger, J. M., DeJager, J., & Taylor, S. E. (2010). Low calorie dieting increases cortisol. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0b013e3181d9523c

Troisi, J. D., & Gabriel, S. (2011). Chicken soup really is good for The soul: Comfort food fulfills the need to belong. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e634112013-630

Tsenkova, V., Boylan, J. M., & Ryff, C. (2013). Stress eating and health. findings from MIDUS, a National Study of US Adults. Appetite, 69, 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.05.020

Van Cauter, E., & Knutson, K. L. (2008). Sleep and the epidemic of obesity in children and adults. European Journal of Endocrinology, 159(suppl_1). https://doi.org/10.1530/eje-08-0298

van der Valk, E. S., Savas, M., & van Rossum, E. F. (2018). Stress and obesity: Are there more susceptible individuals? Current Obesity Reports, 7(2), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-018-0306-y

Xiao, Y., Liu, D., Cline, M. A., & Gilbert, E. R. (2020). Chronic stress, epigenetics, and adipose tissue metabolism in the obese state. Nutrition & Metabolism, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-020-00513-4

We Americans sure do like American things.