Can you cook pasta without boiling water?

The short answer

Yes, the key chemical reactions that cook pasta happen at around 180°F (82°C), below the boiling point of water (212°F (100°C)). But cooking pasta at this lower temperature will require you to cook for a longer time.

The long answer

On the package of your favorite dried pasta, you're likely to find the words: "Bring the pot of water to a boil."

But does it have to be boiling? Could a lower temperature cook pasta just as well? Let's dig in.

What is pasta?

"CSIRO ScienceImage 11385 Pasta made from durum wheat" by CSIRO is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Pasta is made from flour and water (and sometimes eggs). It has two basic elements: carbohydrates in the form of starch and protein in the form of gluten.

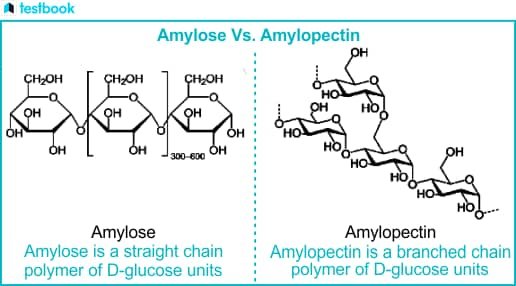

The starch comes in two types: amylose (linear chains of glucose) and amylopectin (branched chains). These starch molecules are embedded within a gluten protein network, which gives pasta its structure.

Source: Testbook

What does it mean to cook pasta?

Cooking pasta involves using heat and water to rehydrate it and trigger two key chemical reactions.

Stage #1: Starch gelatinization

In hot water, starch granules absorb more and more water until they finally burst like a balloon. This burst releases some starch molecules into the water, which is why pasta water appears cloudy. This process is known as starch gelatinization.

Source: greek chemist in the kitchen

That's why pasta tends to stick together early in cooking. The initial release of starch molecules acts like a glue that binds pasta pieces together.

Stage #2: Protein denaturation

While the starches in the pasta continue to absorb more water, the gluten protein structure also starts to transform as a result of the heat. Heat causes the protein’s folded structure to unravel into long amino acid chains, in a process known as protein denaturation.

"Process of Denaturation" by Scurran15 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

This chemical reaction allows the protein to add a mesh structure to the swollen starch molecules that prevents major leaks of starch into the water.

When the pasta is done cooking, the result is a rehydrated piece of starch and gluten that is pliable, moist, and strong enough to maintain its shape. In the words of Italian grandmothers everywhere, you're aiming for the pasta to be al dente, soft but with a bite.

Do you need boiling water to cook pasta?

In theory, you don’t need to reach 212°F (100°C) to trigger starch gelatinization or protein denaturation. Interestingly, both of these cooking processes occur at around 180°F (82°C), below water's boiling point.

But theory alone won't put food on the table, so I put it to the test. Here's how I ran my pasta cooking temperature experiment:

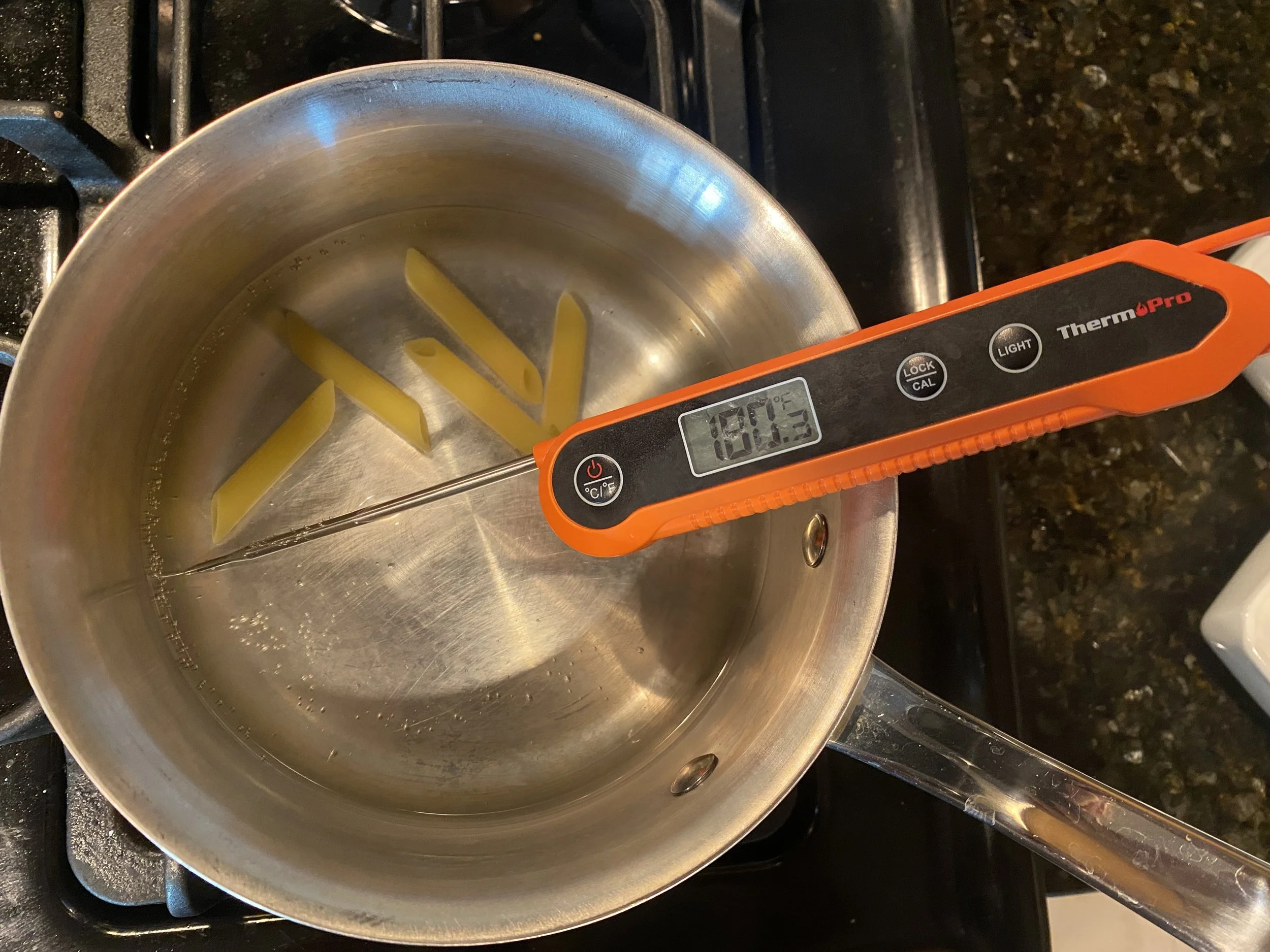

Hypothesis: Cooking pasta at 180°F (82°C) will result in similar outcomes as the control (cooking pasta at 212°F (100°C)) since the former temperature is the minimum required for the key chemical reactions.

Materials: 15 pieces of dried durum wheat penne pasta; 1 cooking thermometer (thanks for the loaner, Kritika! 👋); 1 pot; 1 jar; 6 cups of water.

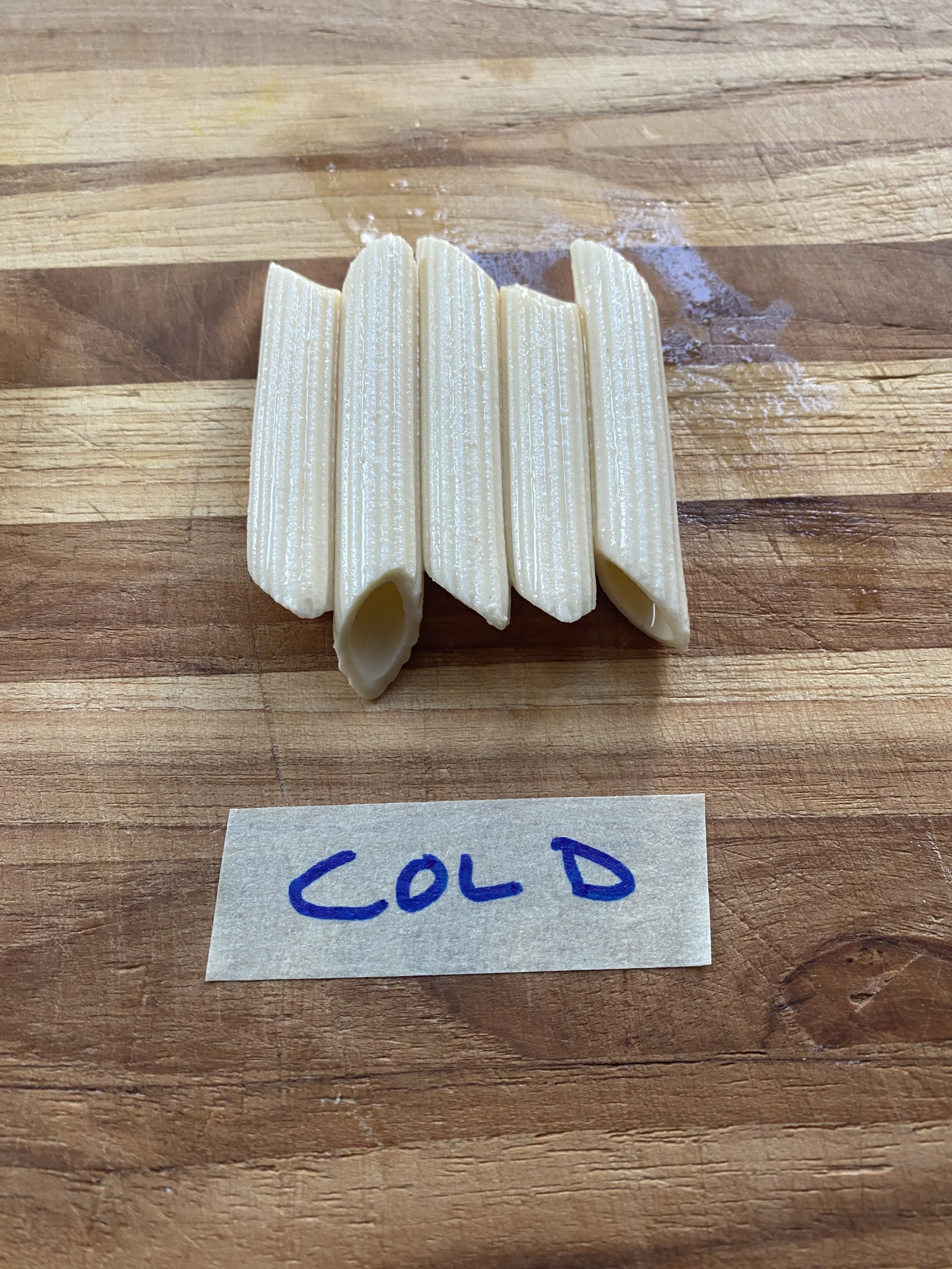

Methods: In a fresh pot of water, I heated the temperature to 212°F (100°C) before adding in 5 pieces of pasta and cooking for 11 minutes (per package instructions), stirring every so often. I repeated the same process at 180°F (82°C), and let both sets of pasta cool to room temperature. Because I was curious, I also cold-soaked pasta in a jar in the refrigerator (~40°F (4°C)) for ~10 hours to see what pasta that experienced rehydration without the key chemical reactions would taste like.

Here's what the pastas looked like after running the experiment. The pastas cooked at 212°F (100°C) and 180°F (82°C) both appeared similar in color and had the same texture on the outside. Comparatively, the cold-soaked pasta was much lighter in color and felt slimy, indicating that starch gelatinization hadn't occurred. When starch is ungelantized, starch molecules haven't been released, so they are less translucent than cooked pasta.

When the pasta was cut, key differences were revealed. The control pasta cooked at 212°F (100°C) was mostly cooked all the way through, reaching al dente. The pasta cooked at 180°F (82°C) was less cooked and still was underdone deeper in the pasta. The cold-soaked pasta was soft all the way through and less bouncy.

When each of the pastas were tasted (by me and my lovely co-researcher Saurav 💕), it was concluded that the 180°F (82°C) had some the characteristics of starch gelatinization and protein denaturation (i.e. it had bounce, shine, and pliability) but it likely needed more time to cook all the way through. The cold-soaked pasta was hydrated but undesirable.

Summary: You can properly cook pasta at a temperature at or above 180°F (82°C), but it will take more time to cook all the way through.

As for me, I'll likely continue to cook at a boiling temperature simply because it's an easy visual cue that the water is hot enough (and I've got to return this cooking thermometer).

🧠 Bonus brain points

Does pasta cook differently at high altitude?

Yes, pasta cooks more slowly at high altitudes because water only boils at 212°F (100°C) ... at sea level. At higher elevations, it boils at a lower temperature.

A brief refresher on the science of boiling: Liquid water turns into gas (i.e. boils) when its molecules have enough energy to spread out and form bubbles. These bubbles rise to the surface and release water vapor.

When you go up higher, there is less air pressure pushing down on the water, which makes it easier for these bubbles to form. This makes the boiling point of water lower than at sea level. If that explainer didn't click for you, this video does a great job visualizing how atmospheric pressure affects boiling.

When you boil water at high elevations, the water hasn't reached 212°F (100°C), which is why it's recommended to add 15-20% more cooking time to your pasta cooking.

Curious about how the world works?

Today You Should Know is a free, weekly email newsletter designed to help you learn something new every Friday.

Subscribe today 👇

Check out some other curious questions:

Sources

Earl, M. (2025, April 15). How to Cook Pasta, Better. ThermoWorks. https://blog.thermoworks.com/how-to-cook-pasta-better-2/

Epstein, K. (2018, March 3). Cooking pasta. Mountain Mama Cooks. https://mountainmamacooks.com/tips/cooking-pasta/

Libretexts. (2023, January 30). Boiling. Chemistry LibreTexts. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Supplemental_Modules_(Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry)/Physical_Properties_of_Matter/States_of_Matter/Phase_Transitions/Boiling

Libretexts. (2024, January 17). 6.3: The Role of Proteins in Foods- Cooking and Denaturation. Medicine LibreTexts. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nutrition/Human_Nutrition_2020e_(Hawaii)/06:_Protein/6.03:_The_Role_of_Proteins_in_Foods-_Cooking_and_Denaturation

Liokatis, A. (2020, January 27). The thin white line. GreekChemist Kitchen. https://www.greekchemistinthekitchen.com/post/pasta-al-dente

López-Alt, J. K. (2024, January 12). A New Way to Cook Pasta? | The Food Lab. Serious Eats. https://www.seriouseats.com/how-to-cook-pasta-salt-water-boiling-tips-the-food-lab

National Center for Families Learning. (n.d.). Why Does Water Boil Faster at Higher Altitude?. Wonderopolis. https://wonderopolis.org/wonder/why-does-water-boil-faster-at-higher-altitude

It’s like an American accent but with calendars.